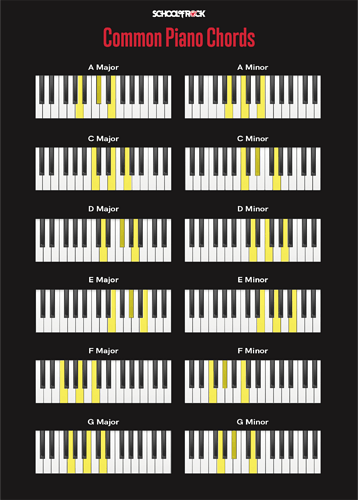

Another piece of (general) advice: stop trying to figure out music theory on stringed instruments and use a keyboard instead. It’s a thousand times easier and more visual to learn this on a piano than a guitar.

Yes! This is weird and confusing. My issue is the words we use to explain these things.

Instead of identifying keys by “major key” or “minor key” it helps to think of them as

“the key signature with these 7 notes” vs a key signature with any other 7 notes.

If you treat every note equally, you can start to explain modes more easily, and how you can develop 7 chords, scales and different sounds with that combination of notes.

Calling a key a major key instantly makes it difficult to describe the inclusion of minor and diminished elements!

Man, that’s the best explanation to what a “key” is, ever.

Why do we tend to complicate things?

Maybe some think it will impress people more.

Look at the SBL lessons, compared to B2B. When I was checking out sites for Bass lessons the first couple of minutes of just about every one of the SBLs videos seemed to be all about Scott and what he could do. ![]() What a waste of time.

What a waste of time.

That’s it. Scott is a real wafflemonster and it puts me off his course. I’m unlikely to sign up for any course. But if I did, Josh’s would be up there as one of the main contenders. From his You Tube vids I think Josh’s approach is more down to Earth and he gets to the point a lot more quickly than most. The production with the various Josh clones is a nice touch and adds value.

Josh also has more visuals such as chord diagrams and notation/tabs for basslines, and this helps the more visual amongst us.

Scott will play away and expect everyone to have the patience to be constantly stopping, rewinding and restarting the vid to see exactly where he’s playing. The fact that he wears gloves for his condition makes things twice as difficult.

Yes! This is weird and confusing. My issue is the words we use to explain these things.

Instead of identifying keys by “major key” or “minor key” it helps to think of them as

“the key signature with these 7 notes” vs a key signature with any other 7 notes. If you treat every note equally, you can start to explain modes more easily, and how you can develop 7 chords, scales and different sounds with that combination of notes. Calling a key a major key instantly makes it difficult to describe the inclusion of minor and diminished elements!

I guess I need to go back a step. What is it that makes something “major” vs “minor”? Is it just an arbitrary label we use, or is their some special tonal quality to “minor” vs “major”. Is that a function of whole/half steps? I suspect its the latter, but my brain wants some sort of consistent mathematical explanation/pattern related to the number of whole/halfsteps.

I also keep wanting to relate “minor” to “accidentals”, i.e. sharps and flats, (like “black keys on the piano are minor”) but that is not true (e.g. A minor).

ding ding ding.

The scales have different tonal qualities, and what defines those qualities is the pattern of the intervals between the notes.

For a major scale, this pattern is always wwhwwwh, regardless of the major key; the minor scale pattern is whwwhww. Just looking at that will tell you nothing about the tonal quality though; you need to play the major scale and minor scale and compare them, for how they “feel”.

You could also describe this as the minor scale having a flattened third, sixth and seventh compared to the major scale for a key, but really what matters are the intervals, and how they sound.

At least that’s how I’ve always thought about it. @Gio can give a more nuanced answer.

Cool. Good info on the scales. I understand that a minor “chord” is a major chord with a flattened 3rd. But how does that relate to calling an interval a “minor” interval? That is the part that seems arbitrary to me.

Part of my confusion is that these terms are used to describe intervals, scales, and chords—and I can’t seem to figure out the common thread linking them.

For instance, a common definition is “A minor interval has one less half step than a major interval.” Ok, but then what makes a “major” interval “major”? I.e. the terms are always described in relation to each other, not as possessing some fundamental, independent, identifiable quality other than “minor is darker.” (which doesn’t always hold true, especially when taking modes into account)

This is not always super clear-cut, but it starts with looking at the “one-step” distance, and then adjusting for the “half-steps” - maybe this helps a bit:

| Number of half-steps | Interval | example | also |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | prime | C-C | |

| 1 | minor second | C-Db | C-C#: augmented prime |

| 2 | major second | C-D | |

| 3 | minor third | C-Eb | C-D#: augmented second |

| 4 | major third | C-E | |

| 5 | perfect fourth | C-F | |

| 6 | augmented fourth | C-F# | C-Gb: diminished fifth |

| 7 | perfect fifth | C-G | |

| 8 | minor sixth | C-Ab | C-G#: augmented fifth |

| 9 | major sixth | C-A | |

| 10 | minor seventh | C-Bb | C-A#: augmented sixth |

| 11 | major seventh | C-B | |

| 12 | octave | C-C |

Something has to be the baseline for comparison; generally the major scale is that base and everything is related to it.

I am not sure why the terms “major” and “minor” were originally chosen.

Thank you; very helpful.

Here is a “putting it all together” conundrum I struggle with.

Lets assume we are in the key of A minor. And lets assume that the song starts on the A chord and has a bass riff into. If I am writing the riff, am I limited to notes on the A minor scale or the A minor chord, etc.? Likewise, if the song then progresses to a “D” chord within the A minor scale, what notes “fit” now?–Still anything on an A minor scale, or just permutations of a D chord or a D (major/minor) scale?

I realize this a question for @howard , but maybe I can chime in…

First off, as the saying goes “there are no bad notes, just bad resolutions” - but, I know what you mean.

You will be fine with taking the notes from an A minor arpeggio (A - C - E - (G)) or the A minor (aeolian) scale (A-B-C-D-E-F-G).

Once you get to the D chord (and unless it is specified more, we must assume it is a D major chord), it would be a chord that is NOT diatonic to A minor (i.e., they don’t share all the same notes). You could then choose from the D major scale (D-E-F#-G-A-B-C#).

To have more notes in common, you could choose to play the dorian scale over the A minor chord (A-B-C-D-E-F#-G).

However, most likely that you will not encounter a D chord, but a D minor chord in the scenario you described, and then you could actually take from the C major scale as both D minor and A minor are diatonic to C major.

It takes some mulling over this, but I am sure it will make sense at some point ![]()

Some things in music can be initially difficult to grasp, so you’re not on your own. It took me quite a while before I could fully digest and understand modes(the M word!), despite them being a simple idea. They weren’t something that I could touch and feel and see, but were more akin to understanding why one’s girlfriend or wife says “fine !!!” after doing nothing whatsoever. I was supposed to understand, but I didn’t.

I realise that with modes that there are other musical ideas that I had to understand first before the eureka moment finally arrived. It will be the same for you regarding major and minor. You don’t need to concern yourself with the M word at the moment, just be aware that they exist and that you will come across them later on.

As howard et al have mentioned, major and minor intervals comes from the idea of whole/half step. But you don’t have to worry about thinking in those terms because it’s the root idea, in the same way that you don’t have to think about contouring your mouth into different shapes to make a sound when you speak.

When we’re talking about major and minor, all the intervals are relative to the root note that is being used at that time. For example, if we’re playing the D major chord, the root note is D. The major 3rd from D will be the note F#. The minor 3rd from D will be F. Again, we know that this is true because of the whole/half step pattern - this: wwhwwwh - that is always true for a major scale(there are other major scales when you come across the M word that have a slightly different pattern, but don’t worry about that yet. For the most commonly used major scale which is just called “the major scale”, the pattern for your intervals is always wwhwwwh).

I suggest you put on a chord drone (you can find them on YT) and experiment by playing notes over the chord.

And check out this video Creating Basslines Over A Chord Progression (Bm/G/Em/C)

This is exactly the reason my brain isn’t able to handle well keyboard instruments … The differentiation between white and black keys, and their size, makes my brain thing about the keyboard in hierarchial way. Like white keys are superior to black keys. On the other hand, fretboard with simple line of tones makes so much more sense.

Yeah. C#maj is way harder to play than Cmaj, for example.

The other nice thing about bass is that you only need to memorize a couple patterns and they move everywhere. Boom, you know all the major scales and minor scales.

Keys - I never bothered memorizing them all, I just figure them out when I need the ones I don’t remember.

On the other hand, it’s way easier learning music theory on keys. Like night and day different.

I was absolutely lost tbh. until one guy mentioned “D as “dam”, D key looks like a dam” … from the moment when one has absolutely unshakable “anchor” on the keyboard all the learning was much smoother