hey y’all.

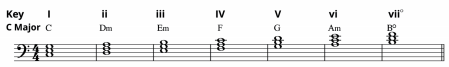

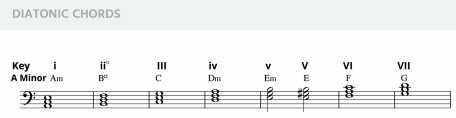

@JimP identified the diatonic chords in a minor key correctly.

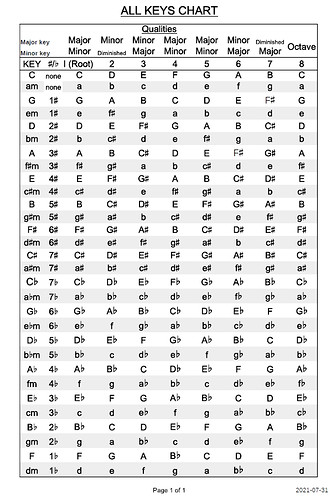

A minor and C major share a key signature.

The root notes and chord qualities all line up and will be the same - the only thing that changes are the numerals.

Warning - I get a bit Theory Wonky here. I love this stuff. Hope it is illuminating.

The reason that there are 2 different V chords listen in the minor key is because…

There is no leading tone in the natural minor mode.

Meaning, scale degree seven in a minor key (G in the key of a minor) is a whole step away from A.

In the major mode, the leading tone (scale degree 7) is a half step away from the root. That half step momentum/tension is what drives the majority of western harmony. The leading tone (and the harmony that it produces) is what drives the ear back home.

Because the natural minor mode didn’t have that, composers just forced it.

They used the G# (in the key of a minor) so that they could drive the ear into the a, and make a feel like home.

The most common way this is done is with the 5 chord.

In the key of a minor, the 5 chord is E.

The naturally occurring chord in the key signature is an E minor chord, but that chord doesn’t create a bunch tension and push the ear back to A.

So.

They pushed the G into a G# and created a major triad on the E. If you build a 7 chord there (better for creating tensions and pushing for a more satisfying resolution) you’d get an E7 chord.

That switch from the G to the G# was done for the effect of making A minor feel like home - like the perfect resolution for the music.

It’s not in the key signature, but has to be done in order for the mechanics of western classical music theory and harmony to work.

Because of this change, people called a minor scale with a G# (instead of a G) a harmonic minor scale. The harmonic minor scale is a completely abstract construct generated by looking at this altered approach to the HARMONY of the minor key.

Composers couldn’t handle the melodic leap from a b6 to a major7. It sounded abominable to the ears of 17th & 18th century Europe.

Composers couldn’t do it.

So… they changed scale degree 6 in their melodies so that they didn’t have to deal with that real cool (to my ears) 1.5 step leap from b6 to 7.

The scale created by analyzing this melodic choice (motivated solely by the inability of old-time composers to hear the ‘exotic’ sound of the b6-major7 leap as good) is called the melodic minor scale.

It’s another abstract concept generated from looking at the melodic movements of Classical music composers through the ages.